long post

Because bus routing is presenting lately as a highly confusing topic, I thought it might help cut through some of the confusion to take apart the way that my MixerChannel class organizes buses and groups.

Some observations up front:

- The MixerChannel design stabilized around 2005 – 17 years ago. It’s robust – it handles everything I can throw at it. It’s reliable – more than a decade and a half of testing.

- You can use or adapt parts of this design as needed. I’m not going to discuss every feature of the MixerChannel design, just how it uses groups and buses.

- IMO following this design carefully is likely to avoid mistakes. (But, no guarantees – being unsystematic or sloppy is likely to cause mistakes!)

Basic principles

- Every channel lives on a bus. Period. No loose signals going directly to bus 0.

- The channel maintains its signal on its own bus.

- The channel also copies that signal to an output target, where it may be mixed with signals from other channels.

- Because order of execution is important, the entire channel is wrapped in a Group.

- And, because source synths should come before effect synths, it’s helpful to have two groups inside of the channel’s group – the first for sources, the second for effects.

Support synths

The channel is responsible for volume control and panning, as well as routing. You need a SynthDef for this.

A send is simpler – doesn’t need panning, and doesn’t need to write back to the original bus. A send will be used later, but I’ll introduce the SynthDef now.

You might think it’s easier to include additional Out units in all your SynthDefs. It’s not. I find it’s much easier to modularize the design. Source SynthDefs are only responsible for generating a signal and putting it onto the channel’s bus. The channel architecture is responsible for forwarding the signal to channel and send targets.

(

SynthDef(\mixer2x2, { |inbus, outbus, level = 1, pan = 0|

var sig = In.ar(inbus, 2);

sig = Balance2.ar(sig[0], sig[1], pan, level);

ReplaceOut.ar(inbus, sig); // "maintains on own bus"

Out.ar(outbus, sig); // "copies to an output target"

}).add;

)

(

SynthDef(\send2x2, { |inbus, outbus, level = 1|

var sig = In.ar(inbus, 2);

sig = sig * level; // DAW sends do have a level control

Out.ar(outbus, sig);

}).add;

)

Channel design

// let's make a channel

// obviously this needs a bus

~srcBus = Bus.audio(s, 2);

// to keep node order clear, let's also make groups

// 1. A group for everything on this channel, including faders

// 2. A group for source synths

// 3. A group for fx inserts

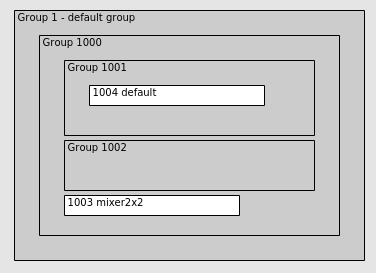

~srcGroup = Group.new;

~srcSynthG = Group.head(~srcGroup);

~srcFxG = Group.after(~srcSynthG);

// and the fader comes at the end

~srcFader = Synth(\mixer2x2, [inbus: ~srcBus, outbus: 0],

target: ~srcGroup, addAction: \addToTail);

To play something into this design, it’s necessary to specify the target group and signal bus. (I’ll admit that this is annoying for plain SC objects. MixerChannel provides convenience methods play and playfx which handle SynthDef names, functions and patterns.)

(instrument: \default, sustain: 1, group: ~srcSynthG, out: ~srcBus).play;

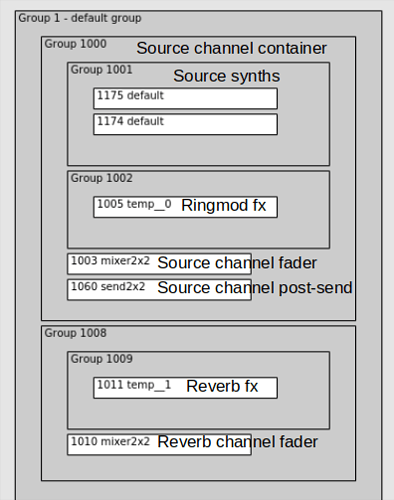

And the node tree looks like this. Because the synth went into the right group, it’s guaranteed to be evaluated before the fader synth. (This is related to the point about consistency: If you put things in the right place, then you get a good result. If you start thinking “well, what if I cheat here or don’t allocate that there, or leave out this arg,” then things will start to go wrong. At that point, the solution is not to try to make the cheat work. The solution is to go back to known principles that will ensure correct results.)

FX inserts

In a DAW, FX inserts are part of the channel. So, here, we play FX synths into the effect group (so that they are guaranteed to follow audio sources).

FX synths should ReplaceOut onto the same bus (“The channel maintains its signal on its own bus”).

(

~ringmod = { |bus|

var sig = In.ar(bus, 2);

sig = sig * SinOsc.ar(90);

ReplaceOut.ar(bus, sig)

}.play(target: ~srcFxG, outbus: ~srcBus, args: [bus: ~srcBus]);

)

(instrument: \default, sustain: 1, group: ~srcSynthG, out: ~srcBus).play;

FX sends

For effects like reverb, where 1/ multiple channels might mix down into the same effect and 2/ the effect will be mixed in with the dry signals, DAW-style sends are the best way.

A send needs another channel, so I’m copying the bus, group and fader code (although I’m leaving out a source-synth group, because the send channel should receive audio from other channels).

It’s also important for the send to come after any channels that are feeding into it. This is why each channel gets its own enclosing group: just move the outer group, and the order is fixed.

Finally, the source channel needs to split the signal off to the send target bus. That’s the purpose of the \send2x2 SynthDef. Most DAWs create post-fader sends by default. You do this literally exactly how it sounds: there is a fader synth, and you put the send synth after it. (If you needed a pre-fader send – guess what! – you put the send synth before the fader. That simple.)

// reverb as send

// a send channel needs a new bus

~rvbBus = Bus.audio(s, 2);

// and at least a main group, and fx group

~rvbGroup = Group.new;

~rvbFxGroup = Group.head(~rvbGroup);

// and a fader synth to xfer to the main output

// note here that it is referring ONLY to ITS OWN inbus

// and the desired final output bus

// -- modularity and encapsulation, don't mess with other channels' stuff

~rvbFader = Synth(\mixer2x2, [inbus: ~rvbBus, outbus: 0], ~rvbGroup, \addToTail);

// FX writes back to the same bus

(

~rvb = { |bus|

var sig = In.ar(bus, 2);

sig = FreeVerb2.ar(sig[0], sig[1], mix: 1, room: 0.8, damp: 0.2);

ReplaceOut.ar(bus, sig);

}.play(target: ~rvbFxGroup, outbus: ~rvbBus, args: [bus: ~rvbBus]);

)

// and ensure the reverb comes after the source(s)

~rvbGroup.moveToTail(s.defaultGroup);

// now we need to send the source signal to the reverb channel

(

~srcRvbSend = Synth(\send2x2, [inbus: ~srcBus, outbus: ~rvbBus],

target: ~srcFader, addAction: \addAfter

);

)

Let’s play something and hear the reverb.

(

p = Pbind(

\instrument, \default,

\degree, Pwhite(-7, 7, inf),

\dur, Pwhite(1, 3, inf) * 0.25,

\legato, 0.4,

\amp, 0.2,

\group, ~srcSynthG,

\out, ~srcBus

).play;

)

~srcRvbSend.set(\level, 2); // extreme! lol

p.stop;

Isn’t that too complicated?

True, this is not the simplest way. But recent conversations about bus routing should reveal that taking shortcuts with routing results in either limitations, or confusion.

-

Limitations: The approach here scales up. It’s a bit annoying to rebuild the structure every time by hand, but a helper object (

MixerChannel) makes it more convenient. In particular, the fact that any number of sends can be added or removed at any time greatly increases flexibility. -

Confusion: The best way to avoid confusion with bus routing is to be consistent. Find a way that works, and always do it that way. I modeled this approach after DAW signal routing because DAW signal routing works (and has been refined over more than a half century of recording engineering practice). Choosing a robust and well-functioning model means that a lot of questions and problems simply disappear: the focus is on doing it correctly rather than on seeing what I can get away with.

Hope this is helpful –

hjh